A Patient’s Guide to SLAP (Superior Labral {Labrum} Anterior to Posterior) Tears

The shoulder functions to place the hand in an appropriate position to accomplish tasks. In order to place the hand in a variety of positions, the shoulder requires freedom of motion. Although the shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body, this amount of mobility comes at the expense of stability. The labrum deepens the socket and serves as an anchor for tendons and ligaments.

Acute SLAP tears may be associated with trauma or repetitive use—such as throwing. However, after age 40—tearing of the superior labrum is part of the normal aging process. The biceps tendon attaches to the superior labrum and therefore labral injuries often demonstrate some element of biceps tendonitis.

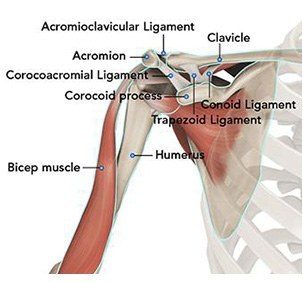

Anatomy

The shoulder serves as a connection between the chest and arm. The clavicle functions as a strut connected to the shoulder bone (scapula). The scapula articulates with the humerus and accounts for approximately 70% of shoulder motion (the remaining motion occurs between the scapula and the thorax). Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

A right shoulder viewed from the front showing the clavicle, humerus and scapula.

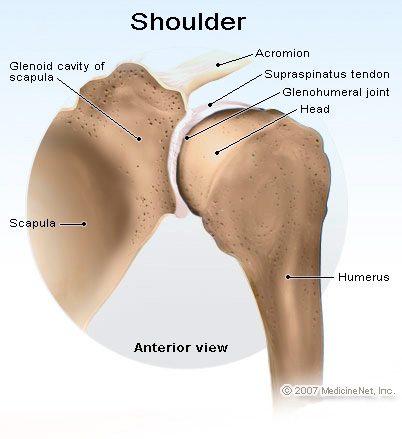

The motion between the shoulder blade and scapula is a stable gliding surface over bursal structures and not prone to dislocation. However, the articulation between the humerus and scapula has little bony stability. This is because the ball of the humerus is large and the socket is small on the scapular side—think of the small amount of stability a golf ball has on a tee.

A right shoulder viewed from behind—note the shallow socket on the scapula articulating with the large ball of the humerus. Because of this lack of bone stability, most stability for the shoulder comes from the surrounding soft tissue—capsule, labrum, and rotator cuff

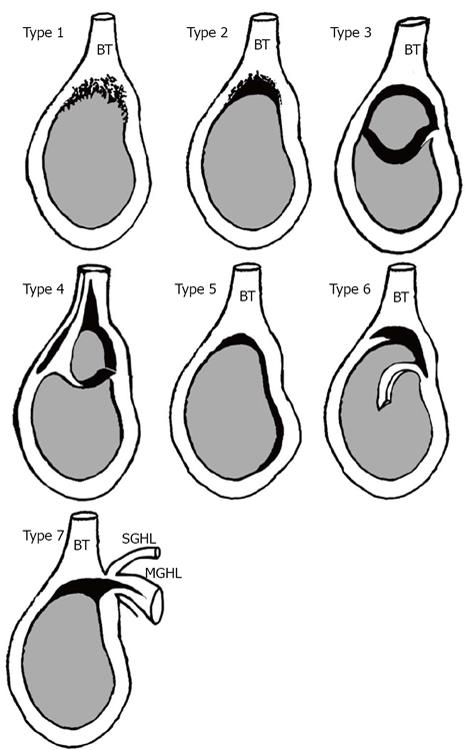

SLAP tears are classified into seven types based on the location of the tear.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The common symptoms of a SLAP tear are similar to many other shoulder problems. They include:

- A sensation of locking, popping, catching, or grinding

- Pain with movement of the shoulder or with holding the shoulder in specific positions

- Pain with lifting objects, especially overhead

- Decrease in shoulder strength

- A feeling that the shoulder is going to “pop out of joint”

- Decreased range of motion

- Pitchers may notice a decrease in their throw velocity, or the feeling of having a “dead arm” after pitching

Physician Examination

After taking a history, your surgeon will examine both shoulders. The range of motion of the shoulders is recorded and any differences from each side. The strength of the shoulder is noted and for patients with atraumatic disorders, an assessment of other joint instability including the elbow and hand is typically warranted.

Specific testing for shoulder instability is them performed. The Speed’s test and Obrien’s test are both specific for labral pathology.

Imaging

X-rays can confirm the direction of dislocation in acute cases. Further, x-rays may reveal bone changes associated with chronic instability—loss of bone stock or avulsion injuries. In cases of chronic injury these studies may be enhanced with MRI imaging of the shoulder which shows the soft tissue components of stability—capsule, labrum, and rotator cuff.

The image shows an MRI demonstrating a superior labrum tear of the shoulder

Treatment

Nonoperative

Most cases of SLAP injuries respond to nonoperative treatment. A course of anti-inflammatory medication is often utilized. These patients often respond to nonoperative treatment including a shoulder strengthen program. These programs may be accomplished at home or under the direction of a physical therapist. Some studies have indicated success in over 80% of patients treated.

Operative

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical methods.

Arthroscopy. The surgical technique most commonly used for repairing a SLAP injury is arthroscopy. During arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your shoulder joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments.

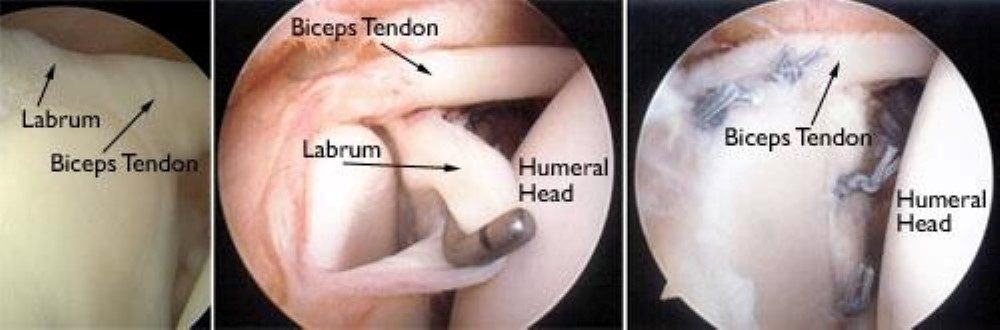

Left image—a normal labral construct demonstrating the attachment of the long head of the biceps to the labrum

Center image—a type III labral tear which is typically treated with surgical excision of the torn portion of the labrum

Right image—a surgical repair of a type II labral tear with anchors and suture repair

Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, your surgeon can use small incisions (cuts), rather than the larger incision needed for standard, open surgery.

Repair options. There are several different types of SLAP tears. Your surgeon will determine how best to repair your SLAP injury once he or she sees it fully during arthroscopic surgery. This may require simply removing the torn part of the labrum, or reattaching the torn part using stitches. Some SLAP injuries require cutting the biceps tendon attachment. After releasing the attachment, the biceps may be released without repair (tenotomy) or tenodesed. Tenotomy leaves a deformity of the biceps, but does not require alterations in demand to allow for healing. Tenodesis may occur in the bicep groove via an arthroscope or below the level of the pectoralis—sub pectoral. Both techniques are utilized and a discussion of which technique is appropriate in your case is part of the discussion.

Failed SLAP repairs often cause continuing pain. If the pain does not resolve with conservative management, repeat surgery is typically indicated which usually does not involve attempts at another labral repair. Typical management includes debridement of the labral repair and tenodesis of the bicep tendon. The majority of patients with revision labral surgery can return to full activity, but a significant portion (approximately 35%) still have symptoms which preclude full activities.

Rehabilitation

After surgery, the arm is typically placed in to a sling to rest. Shoulder motion is begun between 1-3 weeks after surgery and based upon the type of instability. Typically shoulder strengthening is instituted around two months after surgery. Shoulder strength and return to sporting activities begin 4-6 months post-surgery. Many studies have shown equally good outcomes for patients doing their therapy at home versus formal physical therapy. Improvements in strength and performance may occur up to one year after surgery. The majority of patients, but not all, will return to full activity after SLAP surgery.