A Patient’s Guide to Scapula (Shoulder blade) Disorders and Snapping Scapula

Introduction

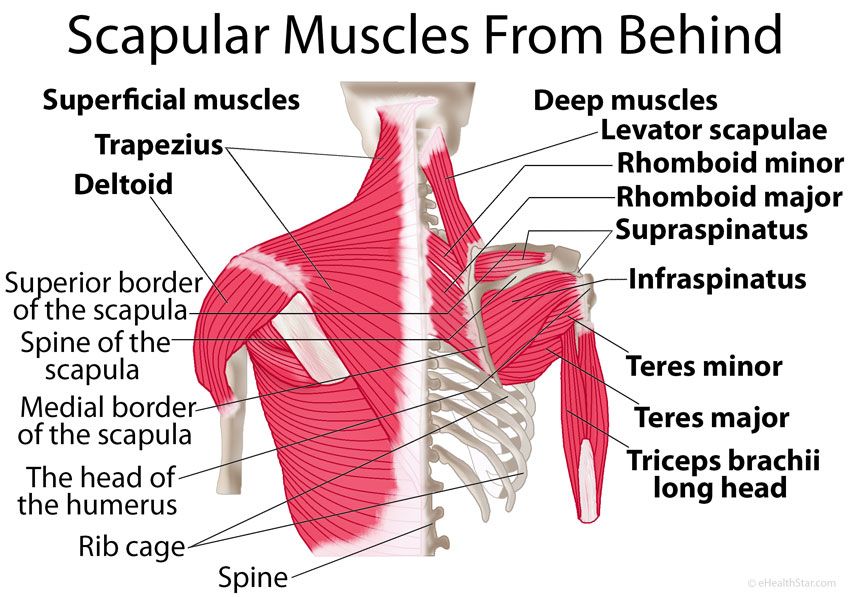

The shoulder blade (scapula) is a large membranous bone involved in shoulder motion and stabilization. The scapulae moves on the back of the chest wall (posterior thorax) to account for one third (1/3) of shoulder motion. Disorders of this scapulothoracic mechanism result in pain, weakness and dyskenesis (painful motion) or the shoulder and shoulder blade. The clicking or grinding may be associated with the disorder and hence the term snapping scapula.

Anatomy

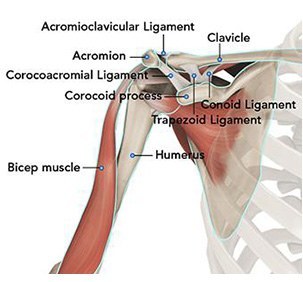

The shoulder serves as a connection between the chest and arm. The clavicle functions as a strut connected to the shoulder bone (scapula). The scapula articulates with the humerus and accounts for approximately 70% of shoulder motion (the remaining motion occurs between the scapula and the thorax). Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

A right shoulder viewed from the front showing the clavicle, humerus and scapula.

The motion between the shoulder blade and scapula is a stable gliding surface over bursal structures and not prone to dislocation. However, the articulation between the humerus and scapula has little bony stability. This is because the ball of the humerus is large and the socket is small on the scapular side—think of the small amount of stability a golf ball has on a tee.

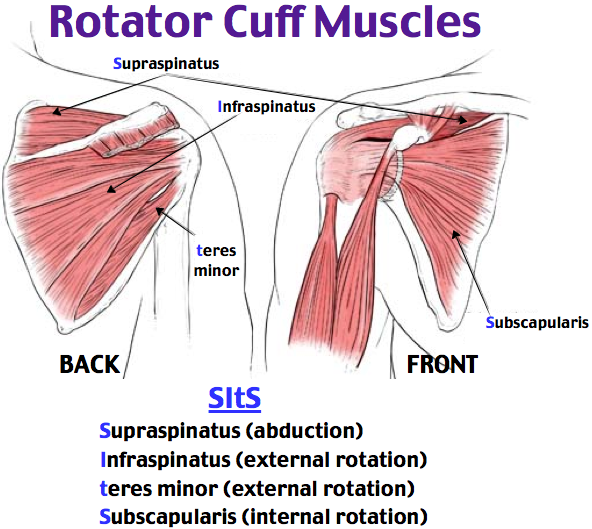

The inside layer of muscles gives the shoulder stability and motion above shoulder height and is called the rotator cuff—a series of 4 muscles

The muscles underlying the deltoid—the rotator cuff viewed from the back and front

The rotator cuff muscles are active especially in activities above shoulder height. These muscles provide the power to effectively function overhead. Rotator cuff tears lead to pain and dysfunction

The scapula and arm are connected to the body by multiple muscle and ligament attachments. The front of the scapula (acromion) is also connected to the clavicle (collarbone) through the acromioclavicular joint.

The scapula serves as a site for the attachment of multiple muscles around the shoulder.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Patients with scapulothoracic disorder often report pain. The pain may be activity related—particularly with overhead activity. The pain is typically along the posterior aspect of the shoulder along the medial border of the scapula. Patients often with snapping scapula complain of popping/grinding or clicking at the scapula.

This is in contrast to Pain with rotator cuff tears is often worse at night. Some studies have suggested this association is because the pain receptors in the shoulder are sensitive to pressure—with these receptors sensing more pressure with patients lying horizontal to sleep, as opposed to upright during the day.

Patients also complain of dysfunction. Many will have difficulty with overhead activities such as changing a lightbulb or reaching into a shelf to get a glass. Complex overhead activities such as throwing a ball may be difficult or impossible. However, activities below the shoulder, such as hitting a golf ball, may continue to be performed—perhaps with less effectiveness.

Surgeon Examination

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, a review of their pertinent medical history and family history is obtained. The range of motion of the shoulder is measured in multiple planes. The strength of the shoulder in resisting motions is tested. The neck is examined to determine if any overlying nerve impingement may be causing shoulder pain and dysfunction. Palpation of the shoulder blade with motion may allow the surgeon to feel the popping/grinding associated with snapping scapula.

Imaging

X-rays of the shoulder are typically utilized for evaluation. Although rare, bony exostosis may arise underneath the scapula causing mechanical irritation of the shoulder blade. Although x-rays do not image the soft tissue of the muscles stabilizing the scapula, they can add information regarding the presence of arthritis, fracture or dislocation.

Typically, advanced imaging such as MRI or CT is not needed for evaluation of scapula disorders or snapping scapula.

Treatment

Nonoperative

Nonoperative treatment is typically successful in treatment of scapular disorders. However, the length of time to accomplish these goals may be lengthy—up to 12-24 months from initial proper diagnosis and treatment. Pain and function can be improved for almost all individuals without surgery.

First line treatment includes the utilization of anti-inflammatory medications (Advil, Aleve). Tylenol may help patient with pain and may be utilized concurrently. For many patients, heat is a useful adjuvant to improve pain.

For patients with continued pain, a steroid injection of the scapulothoracic bursae may be indicated. These injections may be done in connection with mediations listed above. Exercise has proven a helpful adjuvant for rotator cuff tears. Exercise programs can be performed at home or under the direction of a physical therapist–Both methods appear equally effective in studies typically, shoulder steroid injections may be repeated 2-3 times per year. Risks with injection include depigmentation, tendon rupture, and infection.

Operative

Operative management for scapulothoracic disorders is very rare, with most treatments directed at the rare instances of bony exostosis of the shoulder blade. Excision of the bony exostosis may be performed by a shoulder surgeon or a tumor surgeon.

Dr. Groh is an expert shoulder surgeon

- Named top 60 Shoulder Surgeon in the USA by Becker’s Orthopedics

- Active member of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons

- Written 50 Articles and Textbooks on Shoulder Injuries

- Holds patents and developed multiple shoulder implants and devices