A Patient’s Guide to Rotator Cuff Tears

Introduction

The rotator cuff is an integral part of shoulder function. Injury to the rotator cuff is common. Each year there are approximately 2 million physician visits in the USA due to rotator cuff problems. Further, there are approximately 250,000 rotator cuff repairs performed annually in the USA.

Rotator cuff injury causes pain and difficulty with function. Rotator cuff injuries increase in frequency with each decade of aging and are uncommon in teenagers.

Anatomy

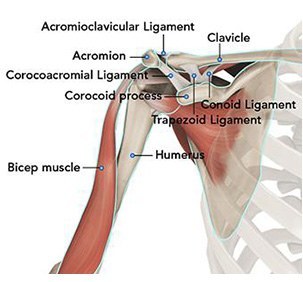

The shoulder serves as a connection between the chest and arm. The clavicle functions as a strut connected to the shoulder bone (scapula). The scapula articulates with the humerus and accounts for approximately 70% of shoulder motion (the remaining motion occurs between the scapula and the thorax). Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

A right shoulder viewed from the front showing the clavicle, humerus and scapula.

The motion between the shoulder blade and scapula is a stable gliding surface over bursal structures and not prone to dislocation. However, the articulation between the humerus and scapula has little bony stability. This is because the ball of the humerus is large and the socket is small on the scapular side—think of the small amount of stability a golf ball has on a tee.

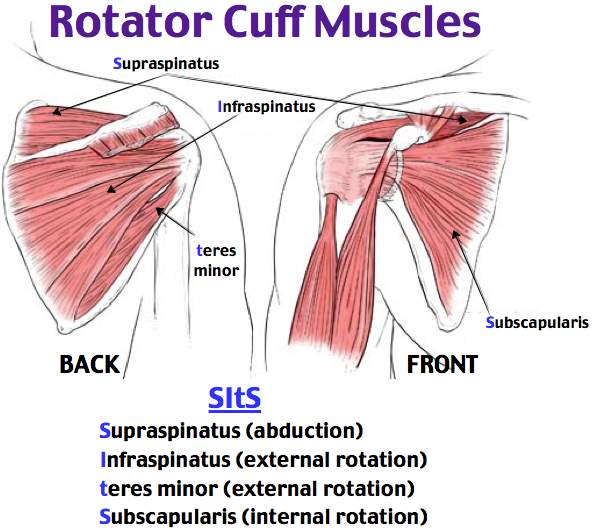

The inside layer of muscles gives the shoulder stability and motion above shoulder height and is called the rotator cuff—a series of 4 muscles

The muscles underlying the deltoid—the rotator cuff viewed from the back and front

The rotator cuff muscles are active especially in activities above shoulder height. These muscles provide the power to effectively function overhead. Rotator cuff tears lead to pain and dysfunction

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Patients with rotator cuff tears often report pain. The pain may be activity related—particularly with overhead activity. Pain with rotator cuff tears is often worse at night. Some studies have suggested this association is because the pain receptors in the shoulder are sensitive to pressure—with these receptors sensing more pressure with patients lying horizontal to sleep, as opposed to upright during the day.

Patients also complain of dysfunction. Many will have difficulty with overhead activities such as changing a lightbulb or reaching into a shelf to get a glass. Complex overhead activities such as throwing a ball may be difficult or impossible. However, activities below the shoulder, such as hitting a golf ball, may continue to be performed—perhaps with less effectiveness.

Surgeon Examination

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, a review of their pertinent medical history and family history is obtained. The range of motion of the shoulder is measured in multiple planes. The strength of the shoulder in resisting motions is tested. The neck is examined to determine if any overlying nerve impingement may be causing shoulder pain and dysfunction.

Imaging

X-rays of the shoulder are typically utilized for evaluation. Although x-rays do not image the soft tissue of the rotator cuff, they can add information regarding the presence of arthritis, fracture or dislocation.

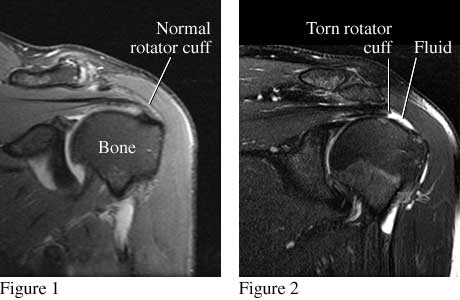

Advanced imaging such as MRI allows accurate representation of the rotator cuff. These studies image the rotator cuff and in cases of a tear can delineate the location, size, and any muscular atrophy associated with the tear.

Figure 1 shows a front view of a normal shoulder and rotator cuff. Figure 2 shows a front view of a shoulder with a torn rotator cuff (supraspinatus tendon).

Ultrasound may be utilized for rotator cuff imaging as well. The results for this imaging compare favorably with MRI and may be done in a physician’s office.

Treatment

Nonoperative

Nonoperative treatment cannot repair a torn rotator cuff. However, pain and function can be improved for many individuals without surgery.

First line treatment includes the utilization of anti-inflammatory medications (Advil, Aleve). Tylenol may help patient with pain and may be utilized concurrently. For many patients, heat is a useful adjuvant to improve pain.

For patients with continued pain, a steroid injection of the shoulder joint may be indicated. These injections may be done in connection with mediations listed above. Exercise has proven a helpful adjuvant for rotator cuff tears. Exercise programs can be performed at home or under the direction of a physical therapist–Both methods appear equally effective in studies typically, shoulder steroid injections may be repeated 2-3 times per year. Risks with injection include depigmentation, tendon rupture, and infection.

Unfortunately, tears of the rotator cuff not treated will progress and become larger over time. Steroids may mask the symptoms or actually causing tearing to progress. Rotator cuff tears which are not treated may become so large that repair becomes impossible over time.

Operative

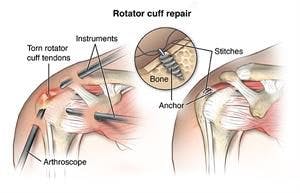

Operative management is indicated for most rotator cuff tears which are amenable to repair. Repair of the rotator cuff can be associated with improvements in pain, function and strength of the shoulder. Effective repairs can be performed in an all arthroscopic fashion.

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair is typically performed as an outpatient surgery. The surgery is typically performed under a regional block and may be accompanied by sedation or general anesthesia. Arthroscopy is performed through poke holes in the shoulder typically no larger in diameter than a pen. The size and location of the rotator cuff tear determines the number of portals, but typically 3 or 4 are required for an average rotator cuff tear.

An arthroscope and instrument inserted into a right shoulder viewed from the side

Most arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs are done with sutures attached to plastic anchors placed into the bone. With healing, the sutures and anchors do not require removal. Plastic anchors do not trigger metal detectors at airport security.

A tear of the rotator cuff repaired with sutures and anchors

Rehabilitation

After surgery the arm is immobilized in a sling to allow for wound healing. Patients report pain after surgery, but the pain generally improves after the second day and utilization of multimodal pain techniques have been shown to improve outcomes for patients. Night pain is typically the most problematic—but multimodal pain programs, heat, and sleeping elevated can improve this difficulty.

Many studies have shown that patients can successfully rehabilitate their shoulder on their own at home. Patients are typically guided through a therapy program and weaned from their sling over the first 8-12 weeks. Ingrowth of the tendon typically requires 4 months and patients may return to golf by 5-6 months after surgery. Continued work on motion and strength allows form improvement for up to 1 year after surgery.

Results for healing are correlated with smaller tear size, no muscle atrophy, and less lamination of the rotator cuff tear. Significant bleeding from arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery is rare. Other low rate complications include infection and nerve injury.

Dr. Groh is an expert shoulder surgeon

- Named top 60 Shoulder Surgeon in the USA by Becker’s Orthopedics

- Active member of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons

- Written 50 Articles and Textbooks on Shoulder Injuries

- Holds patents and developed multiple shoulder implants and devices

WATCH A VIDEO OF AN ARTHROSCOPIC ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR PROCEDURE: