A Patients Guide to Arthritis of the Shoulder

Introduction

In 2011, more than 50 million people in the United States reported that they had been diagnosed with some form of arthritis, according to the National Health Interview Survey. Simply defined, arthritis is inflammation of one or more of your joints. In a diseased shoulder, inflammation causes pain and stiffness.

Although there is no cure for arthritis of the shoulder, there are many treatment options available. Using these treatment options, most people with arthritis can manage pain and stay active.

Anatomy

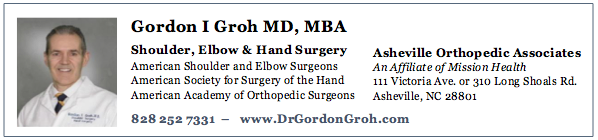

The shoulder serves as a connection between the chest and arm. The clavicle functions as a strut connected to the shoulder bone (scapula). The scapula articulates with the humerus and accounts for approximately 70% of shoulder motion (the remaining motion occurs between the scapula and the thorax). Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

A right shoulder viewed from the front showing the clavicle, humerus and scapula.

The motion between the shoulder blade and scapula is a stable gliding surface over bursal structures and not prone to dislocation. However, the articulation between the humerus and scapula has little bony stability. This is because the ball of the humerus is large and the socket is small on the scapular side—think of the small amount of stability a golf ball has on a tee.

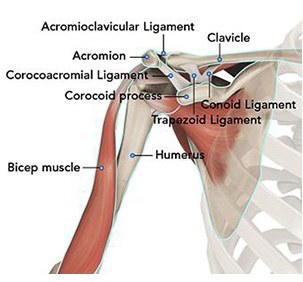

The inside layer of muscles gives the shoulder stability and motion above shoulder height and is called the rotator cuff—a series of 4 muscles.

The muscles underlying the deltoid—the rotator cuff viewed from the back and front

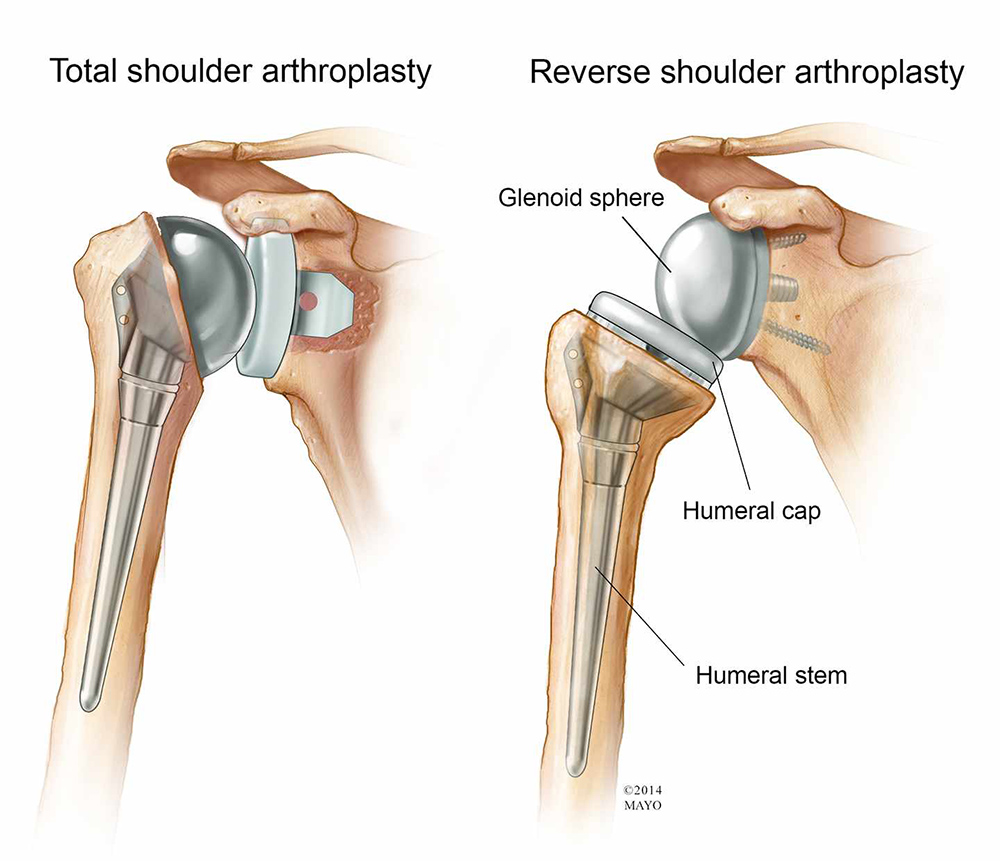

Because of the necessity for the rotator cuff to stabilize the ball of the humerus, an anatomic or standard shoulder replacement is indicated when arthritis of the shoulder is coupled with an intact rotator cuff. This combination is the most common in patients with osteoarthritis.

Five Major Types of Arthritis

Five major types of arthritis typically affect the shoulder.

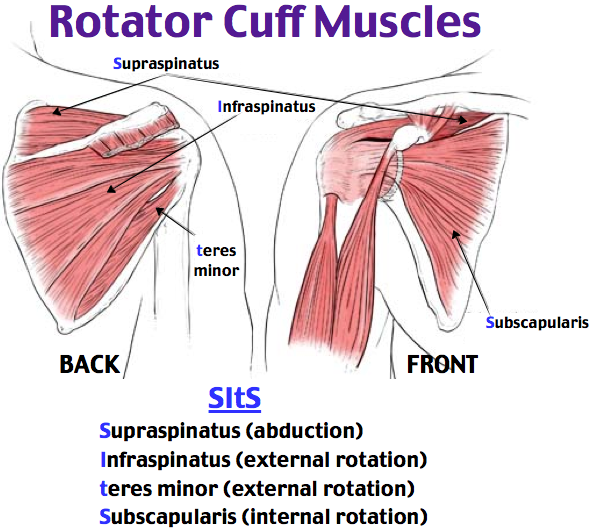

Osteoarthritis

Also known as “wear-and-tear” arthritis, osteoarthritis is a condition that destroys the smooth outer covering (articular cartilage) of bone. As the cartilage wears away, it becomes frayed and rough, and the protective space between the bones decreases. During movement, the bones of the joint rub against each other, causing pain.

Osteoarthritis usually affects people over 50 years of age and is more common in the acromioclavicular joint than in the glenohumeral shoulder joint.

(Left) An illustration of damaged cartilage in the glenohumeral joint. (Right) This x-ray of the shoulder shows osteoarthritis and decreased joint space (arrow).

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease that attacks multiple joints throughout the body. It is symmetrical, meaning that it usually affects the same joint on both sides of the body.

The joints of your body are covered with a lining — called synovium — that lubricates the joint and makes it easier to move. Rheumatoid arthritis causes the lining to swell, which causes pain and stiffness in the joint.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system attacks its tissues. In RA, the defenses that protect the body from infection instead damage normal tissue (such as cartilage and ligaments) and soften bone.

Rheumatoid arthritis is equally common in both joints of the shoulder.

Posttraumatic Arthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis is a form of osteoarthritis that develops after an injury, such as a fracture or dislocation of the shoulder.

Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy

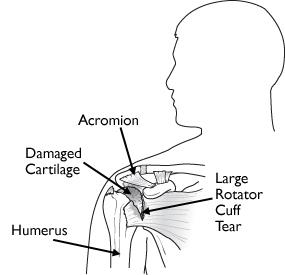

Arthritis can also develop after a large, long-standing rotator cuff tendon tear. The torn rotator cuff can no longer hold the head of the humerus in the glenoid socket, and the humerus can move upward and rub against the acromion. This can damage the surfaces of the bones, causing arthritis to develop.

The combination of a large rotator cuff tear and advanced arthritis can lead to severe pain and weakness, and the patient may not be able to lift the arm away from the side.

Rotator cuff arthropathy

Avascular Necrosis

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the shoulder is a painful condition that occurs when the blood supply to the head of the humerus is disrupted. Because bone cells die without a blood supply, AVN can ultimately lead to destruction of the shoulder joint and arthritis.

Avascular necrosis develops in stages. As it progresses, the dead bone gradually collapses, which damages the articular cartilage covering the bone and leads to arthritis. At first, AVN affects only the head of the humerus, but as AVN progresses, the collapsed head of the humerus can damage the glenoid socket.

Causes of AVN include high dose steroid use, heavy alcohol consumption, sickle cell disease, and traumatic injury, such as fractures of the shoulder. In some cases, no cause can be identified; this is referred to as idiopathic AVN.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Patients report pain and limitation in raising the arm with shoulder osteoarthritis. This greatly limits the function of these patients—many are unable to get a glass from a shelf, comb their hair or reach across the table to grab the salt shaker. Pain may be worse at night and interfere with sleeping.

Surgeon Examination

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, a review of their pertinent medical history and family history is obtained. The range of motion of the shoulder is measured in multiple planes. The strength of the shoulder in resisting motions is tested.

Imaging

X-rays can determine the amount of arthritis associated with the disease. Typically x-rays from multiple angles better discern the amount of arthritis. Patients with chronic rotator cuff tearing may exhibit changes in relationship of the ball and socket which indicates a massive chronic tear with a high riding humeral head. Patients with an intact rotator cuff typically have a head centered on the glenoid.

Enhanced imaging of CT or MRI may be used to further image bone for reconstruction. MRI may be used to evaluate the status of the rotator cuff when it is unclear regarding the rotator cuff integrity. In intact rotator cuff is typically required for anatomic shoulder replacement.

Treatment

Nonoperative

Initial management for shoulder arthritis mirrors osteoarthritis in other joints. First line treatment includes the utilization of anti-inflammatory medications (Advil, Aleve). Tylenol may help patient with pain and may be utilized concurrently. For many patients, heat is a useful adjuvant to improve pain.

For patients with continued pain, a steroid injection of the shoulder joint may be indicated. These injections may be done in connection with mediations listed above. The role of physical therapy for shoulder arthritis remains unclear. Typically, shoulder steroid injections may be repeated 2-3 times per year. Risks with injection include depigmentation, tendon rupture, and infection.

Operative

For patients with continued pain and poor function, shoulder arthroplasty is an option. Results are shown in some studies to correlate with surgeons who do a considerable volume of shoulder replacement every year. The anesthesia choices include regional or general anesthesia. Incisions are required to place hardware for the reverse procedure into position. Dissection to identify nerves and bone landmarks usually makes these procedures done in a hospital setting—although outpatient surgery is reported with good outcomes.

Surgery is typically performed with a nerve block and supplemental anesthesia. Surgery typically requires less than two hours and the risks of blood transfusion are 1% in most studies. The need for medical prevention of deep vein clots after surgery is controversial and ranges from none, to aspirin, to mechanical compression to blood thinning agents. Other standard risks associated with surgery and arthroplasty apply to these types of procedures.

The type of replacement differs for the source of the arthritis. Typically, osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff is treated with a standard (anatomic shoulder replacement. However, some glenoid morphology or patient age may make reverse shoulder arthroplasty an option.

Patients with rotator cuff tear and poor function without arthritis (pseudo paralysis) may be a candidate for reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Also patients with arthritis accompanied by rotator cuff tearing (rotator cuff arthropathy, Milwaukee shoulder) are also good candidates for reverse shoulder replacement. Similarly, most cases of rheumatoid arthritis requiring surgery are optimally treated with reverse shoulder replacement if there is damage or loss of the rotator cuff.

On the left is a standard (anatomic) shoulder arthroplasty. The components of the ball and cup are reversed on the right—a reverse shoulder replacement.

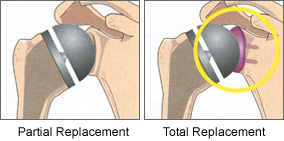

Avascular Necrosis or Posttraumatic arthritis may affect the humeral head only, in these cases a partial shoulder replacement may be indicated. However, a complete replacement may be indicated if glenoid involvement is detected.

A partial shoulder replacement on the left with replacement of the entire humeral head. Alternatively, replacement of only the area with arthritis may be possible in some cases. The right image shows replacement of both the ball and socket (glenoid).

Rehabilitation

After surgery the arm is immobilized in a sling to allow for wound healing. Patients report pain after surgery, but the pain generally improves after the first day and utilization of multimodal pain techniques have been shown to improve outcomes for patients. Most patients will report resolution of their preoperative deep achy pain within the first two weeks and note their pain from the surgery has subsided considerably.

Many studies have shown that patients can successfully rehabilitate their shoulder on their own at home. Patients are typically guided through a therapy program and weaned from their sling over the first 2 months. Ingrowth of the components typically requires 3-4 months and patients may return to golf by 4 months after surgery. Continued work on motion and strength allows form improvement for up to 1 year after surgery.

Dr. Groh is an expert shoulder replacement surgeon

- Named top 60 Shoulder Surgeon in the USA by Becker’s Orthopedics

- Active member of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons

- Written 50 Articles and Textbooks on Shoulder Injuries

- Holds patents and developed multiple shoulder implants and devices including reverse shoulder replacement and standard shoulder replacement