A Patient’s Guide to Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome is one of the most common maladies to affect patients seeing a hand surgeon. The condition is typically manifest by complaints of numbness, tingling and sometimes pain in the affected hand–often the condition is bilateral and may be worse at night.

These symptoms are caused by compression of the median nerve at the wrist. Nerves which are compressed cause these symptoms—with the distribution of the nerve defining the location of the difficulty. The name carpal tunnel syndrome arises from the location of the nerve as it is pinched.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is slightly more common in women versus men. The age distribution of affected patients is wide, although almost all are adults. Some medical conditions may contribute to the disease, but in most cases the cause of carpal tunnel syndrome is unknown (idiopathic).

Anatomy

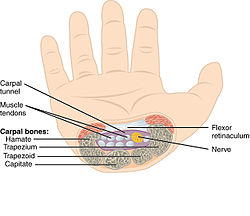

The median nerve, like all other peripheral nerves begins in the spinal cord and accesses the arm via the brachial plexus. As the nerve then travels down the arm, the nerve gains access to the hand at the level of the wrist (carpus in Greek). The nerve travels through a defined space in the bottom (volar) portion of the wrist. This “tunnel” which the nerve traverses is also shared with all other flexor tendons for the fingers and thumb.

The tunnel is formed by the carpal bones on the bottom and the transverse carpal ligament forming the roof. The tendons are lined by synovium and swelling of the synovium is thought to be the inciting factor for the disease. The space is constrained and any swelling of tendons causes compression of the median nerve.

Figure above: A right hand viewed through cross section showing the median nerve within the carpal tunnel. Note the tunnel is bordered by the carpal bones on bottom and the transverse carpal ligament forming the roof.

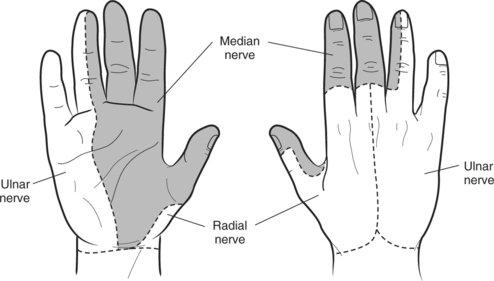

There are three nerves which make a normal hand function. The radial nerve gives sensation to the top of the hand. The ulnar nerve gives sensation to the small finger and part of the ring finger. Classically, the median nerve gives sensation to the thumb, index, middle, and the half of the ring finger on the thumb side. This is the classic distribution and wide variation is known to exist.

Classic innervation of the median nerve shown in grey for the right hand from the bottom and top. Note the distribution for both the ulnar nerve and radial nerve along the small/ring finger and top of hand.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Patients present with complaints of numbness, tingling, and pain in the affected hand. Often the symptoms are bilateral, although one hand may be more affected than the other hand. Patients may complain of night time difficulty with sleeping and awaking often. Patients may describe shaking their hands to alleviate the symptoms. Other patients may report their symptoms are worse with vibratory exposure (weed eater or driving a car).

Although the majority of carpal tunnel cases e idiopathic, any condition which causes swelling of the synovium may incite the condition. Thus patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory conditions may be more likely to suffer from the disease. Other contributing factors may include vibratory exposure, repetitive hand use, or pregnancy.

Hand Surgeon Examination

After determining your symptoms and detailing a history of your difficulties, a physical examination will be performed. Your hand surgeon will note the range of motion of your extremity. Further notice will be focused on the function of the nerves in the extremity.

Nerves give both sensation and muscular strength. How well the nerve functions may be assessed by your ability to determine sharp versus dull or the differentiation of two points. General examination of the hand may detail any muscular atrophy from severe nerve dysfunction. Your surgeon may also test muscular strength and note them for particular nerve function

Special testing for carpal tunnel includes tapping on the nerve at the carpal tunnel eliciting tingling (called a positive Tinnel sign). Other provocative tests for carpal tunnel include pressing on the nerve at the tunnel or flexing the wrist (median nerve compression test or Phalen exam). Importantly, the surgeon may look for negative signs including neck compression (Spurling exam) or thoracic outlet or pronator syndrome.

Compression of the median nerve at the carpal tunnel reproduces symptoms.

Testing

Electrophysiological tests evaluate the ability of the nerve to conduct electrical signals and the ability of muscles to respond to these signals. It should be noted that as in all tests, both false positives and false negatives are present. Therefore these tests are ordered to confirm the presence of carpal tunnel. However, these tests by themselves neither diagnose nor rule out carpal tunnel syndrome. These tests may be conducted by your hand surgeon or these tests may be performed by a neurologist.

Since x-rays routinely have not been found to be helpful in the condition, unless other entities are suspected they typically are not ordered for this condition.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

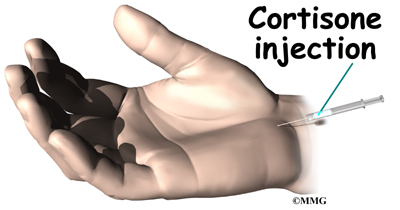

Non-surgical treatment is typically indicated early I the disease or if the carpal tunnel symptoms are mild. Nonoperative treatment is typically more effective in these situations. Activity modifications may be helpful if the patient has vibratory exposure or repetitive hand gripping. Bracing may be utilized by your surgeon and is typically utilized at night for most patients. Bracing may be utilized with a steroid injection into the carpal tunnel. Steroids are ant inflammatory agents and thought to decrease swelling of the synovium. Interestingly, oral anti-inflammatory agents are not thought to be effective for the disease. If symptoms are controlled by these measures, no further treatment is indicated.

Picture of a typical brace worn at night to keep the wrist straight—decreasing pressure on the median nerve.

A steroid injection may decrease selling of the synovium and decrease pressure on the median nerve—relieving symptoms

Surgical Treatment

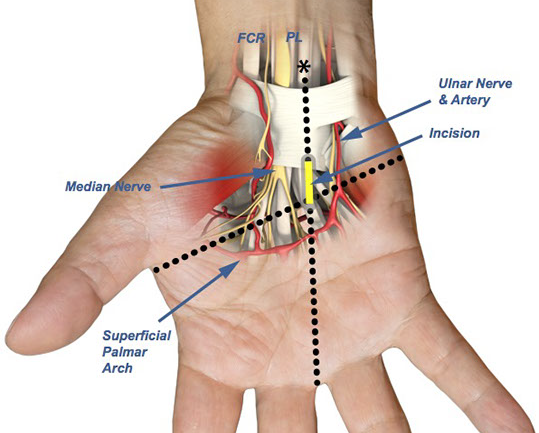

If the patient’s symptoms persist, despite nonoperative management, surgical treatment is the next logical step—called a carpal tunnel release. All surgical management is centered on decreasing pressure on the median nerve at the carpal tunnel. Surgical treatment can be performed as an outpatient surgery, typically using local anesthesia. A small incision is made in the palm of the hand and the transverse carpal ligament is divided releasing pressure on the nerve.

Decreasing pressure on the median nerve is accomplished by releasing the transverse carpal ligament.

The surgical procedure performed for carpal tunnel syndrome is called a “carpal tunnel release.” There are two different surgical techniques for doing this, but the goal of both is to relieve pressure on your median nerve by cutting the ligament that forms the roof of the tunnel. This procedure increases the size of the tunnel and decreases pressure on the median nerve.

A right hand demonstrating the incision and division of the transverse carpal ligament which decompresses the median nerve

Rehabilitation

After surgery, a light wrap will be applied to your hand. In most cases, a dressing change at home 4 days after surgery is used and band aids are used to keep the incision clean and dry. The patient may begin using the fingers and thumb after surgery for light activity and increase activity as tolerated. Sutures are removed in about 2 weeks and continuation of grip strengthening is emphasized.

Night time sleeping is typically the first symptom to improve. Improvement of feeling in the digits moves from the site of incision and marches distally over time. The rate of improvement and overall recovery are inversely related to the severity of nerve pinch and its duration. Pain and discomfort decrease over time after surgery. Most improvement of grip strength returns by 3 months after surgery, but some cases may continue to improve for up to one year. Hand therapy is typically not required after carpal tunnel surgery.

Standard surgical risks for surgery are applicable including infection, bleeding, and anesthetic risks. Most cases do not require prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis.

Surgery for carpal tunnel yields good results in most cases. Results of treatment may be compromised by longstanding nerve compression or other nerve disease. Recurrence after treatment is uncommon, but may respond to additional treatment.