A Patient’s Guide to Arthritis of the Base of the Thumb

Arthritis is a process which causes wear of the smooth lining of the joint called the articular cartilage. This process is progressive and typically intensifies over time. The most common type of arthritis is osteoarthritis—a degenerative arthritis. Other types include rheumatoid arthritis—a type of inflammatory arthritis. The vast majority of patients will have osteoarthritis of the thumb. This arthritis affects the base of the thumb and is also called the carpal metacarpal joint

Anatomy and Arthritis

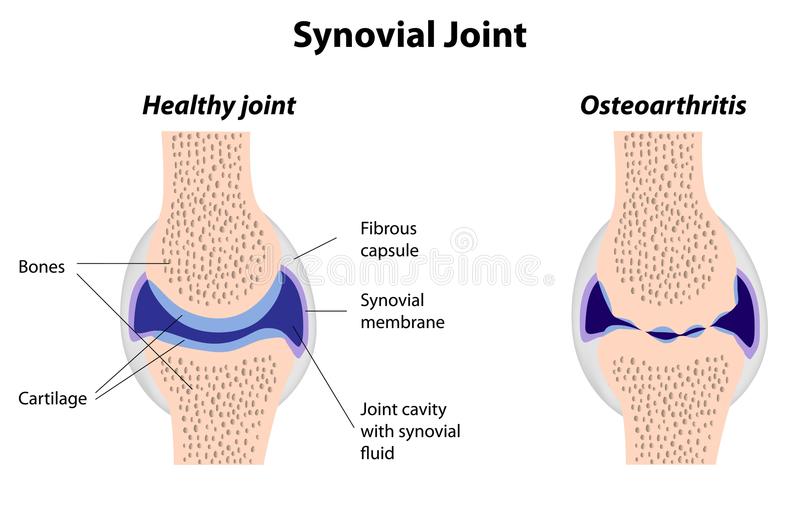

A normal joint consists of matching sets of articular cartilage surface. Cartilage is unique in that it does not have a direct blood supply to nourish the cartilage. Instead, the lining of the joint, called the synovium, secretes synovial fluid which lubricates the joint and nourishes the cartilage. Arthritis therefore is an inflammation of the joint.

A normal joint on the left—note the matching articular cartilage joints. On the right the osteoarthritis joint shows thinning of the cartilage along with incongruity of the joint.

A normal joint on the left—note the matching articular cartilage joints. On the right the osteoarthritis joint shows thinning of the cartilage along with incongruity of the joint.

Articular cartilage covering the end of joints allows them to glide smoothly, much like the Teflon on a frying pan. When there is loss of the cartilage, the joint grinds with motion and causes pain.

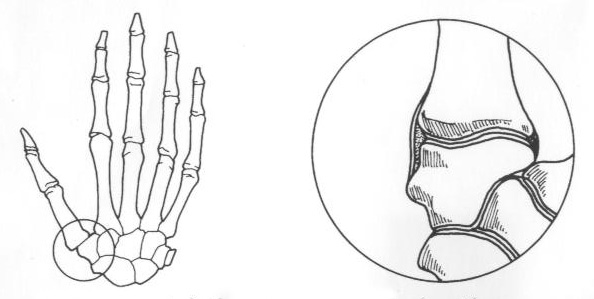

Hand surgeons refer to the thumb as the “king of the digits.” This is because for all activity the thumb must be positioned for effective grip and pinch. The basilar thumb joint acts as a universal joint to position the thumb for activity.

Figure above: The circle shows the areas associated with thumb arthritis—which includes the thumb metacarpal and trapezium.

Osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb occurs in an approximately 3; 1 ratio of women to men. Women are typically affected earlier in life—typically after 40 years of age. Men affected by osteoarthritis typically are symptomatic later in life.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The most constant symptom associated with any arthritis is pain. The pain associated with arthritis may be initially associated with heavy activity. Patients may repot cramping, aching or burning associated with the joint. Often the symptoms occur after the activity has ended and may persist. Many patients will complain of morning pain with osteoarthritis.

The pain associated with arthritis typically progresses. Initial symptoms are then triggered with less activity and the pain becomes more constant. Stiffness of digits is another common complaint—although early in the disease morning stiffness is predominate. Patients with thumb arthritis complain of loss of grip and pinch strength.

Hand Surgeon Examination

After your hand surgeon has reviewed your symptoms, the surgeon may inquire into your family history or related medical history. The surgeon will note the range of motion of joints. Along with motion—examination for crepitance or swelling is included. Any deformity of the joints is noted as some types of arthritis have a particular predilection and progression.

Imaging

Routine x-rays are helpful in determining the health of joints. Healthy joints have appropriate clear spaces between joints inhabited by healthy cartilage. As the cartilage is degraded, this amount of space is decreased and may be accompanied by the development of osteophytes.

X-ray of left thumb showing decreased cartilage space between the metacarpal and the trapezium—there is also subluxation of the metacarpal on the trapezium.

Advanced imaging techniques (CT and MRI) are not often necessary in routine evaluation of arthritis, but may play a role in planning treatment

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies are more helpful in the diagnosis of rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis than in osteoarthritis. Your surgeon may include testing for rheumatoid factor or antinuclear antibodies. However, negative findings for these tests do not exclude inflammatory arthritis as there are seronegative patients with these diseases. Inflammatory arthritis is a clinical diagnosis and patients may require referral to a rheumatologist.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment of thumb arthritis mirrors arthritis treatment for larger joints. Early in the disease activity modification may be helpful. Later stages may respond to anti-inflammatory agents such as naproxen or ibuprofen. Often these medications are coupled with bracing to support the joint. Typically bracing is only utilized for activities which cause discomfort.

Patients who still report pain may benefit from a steroid injection into the joint. Steroids are powerful anti-inflammatory medications and are often quite effective. These medications may be repeated 2 or 3 times per year. Risks of steroid injections may include depigmentation, tendon rupture, infection, and elevation of blood glucose.

Surgical Treatment

Patients who continue to have symptoms in spite of maximum conservative management candidates for surgery. Fusion of arthritis joints can decrease pain, but at the expense of motion—which is critical for good thumb function. More commonly, the trapezium bone is resected and a tendon is used to reconstruct the joint for function and stability.

The Trapezium has been resected and replaced by tendon for osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb.

Most hand arthroplasty surgery can be completed as an outpatient surgery and the majority done under regional anesthesia. For most patients, blood loss is minimal and unless there are medical indications—prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis is not necessary. Other risks of surgery are small and include infection, bone healing, tendon rupture, and stiffness.

Patients are placed into a splint after surgery and typically return in two weeks for suture removal. Patients who receive regional anesthesia report less pain after surgery, but all patients should follow instructions regarding pain medications to improve their postoperative experience. Once patients recover from the surgical pain of application of the hardware, most report considerable improvement in their overall hand discomfort.

Rehabilitation

After surgery patients are instructed in elevation of the extremity and work on range of motion for the digits not affected. At two weeks most patients have suture removal and some are placed into a removable brace. By six weeks after surgery, most patients will have considerable healing and will likely start weaning from the splint. Work on range of motion can be accomplished at home or with the help of a hand surgeon. Strengthening of the hand, wrist, and arm are emphasized and most patients should gain good use of their wrist and hand—especially with diligent work on motion and strength.

Outcomes

Modern hand surgery arthroplasty care has greatly improved the results for patients. Return to sports after surgery typically requires 3-6 months. Patients report continuing improvement for up to one year after injury.